"Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth"

Franklin D. Roosevelt

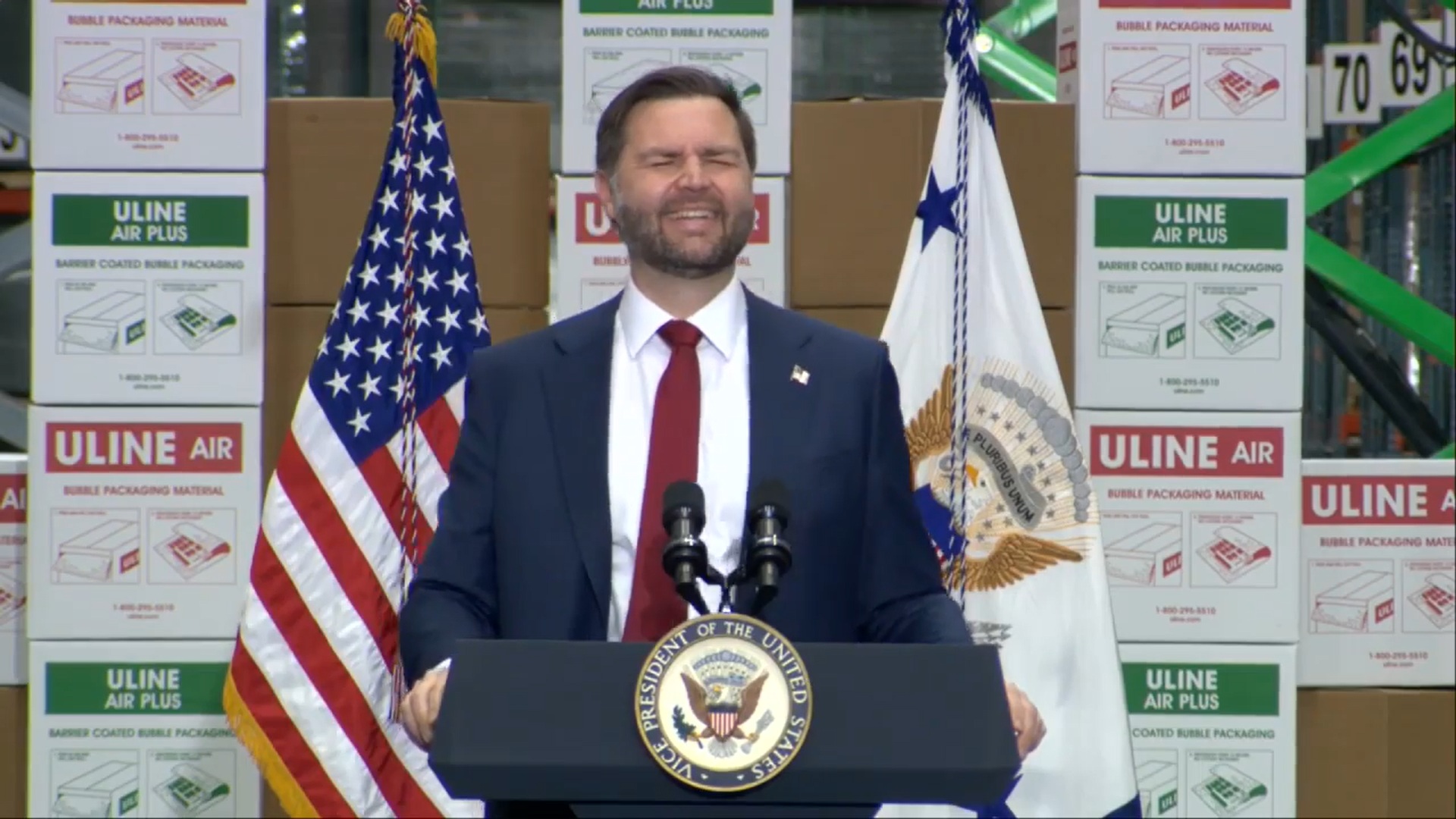

US Vice-President Embraces the “Crazy Conspiracy Theorist” Label

The verdict comes from the most powerful figure in the White House after Donald Trump. In Vanity Fair, Susie Wiles — the president’s chief of staff — described Vice President JD Vance as a “conspiracy theorist for a decade.” In the same profile, she labelled White House Office of Management and Budget director Russell Vought “a right-wing absolute zealot,” referred to Elon Musk as an “avowed ketamine user,” and was sharply critical of Pam Bondi’s handling of the Epstein files.

The remarks, striking for their bluntness and later downplayed by Wiles as having been taken out of context, earned her no reprimand.

Asked publicly the same day to respond to Wiles’s comment about him, Vance did not deny it. He burst into a suppressed laugh, conceded that he was indeed, “sometimes,” a conspiracy theorist — and immediately added: “But I only believe in the conspiracy theories that are true.” The line drew loud applause from his audience.

Vance then proceeded to deploy a well-worn piece of sophistry: the straw man. The technique consists in distorting the accusation directed at you — or your critic’s argument — in order to refute it more easily. It is a familiar pattern. Vance has previously described one of the world’s most notorious conspiracy-driven disinformation peddlers, Alex Jones, as a “truth-teller.” Despite the absence of any evidence of massive electoral fraud, he also subscribes to the Trumpian lie that the 2020 presidential election was “stolen” and deliberately rigged.

JD Vance was also the first major MAGA political figure to popularise the racist conspiracy theory claiming that Haitian migrants in Springfield, Ohio, were “eating cats and dogs.” Entirely unfounded, the allegation circulated initially in fringe online spaces before being amplified by Vance — and only later taken up and repeated by Donald Trump himself during the 2024 presidential election campaign. The episode offers a textbook illustration of how conspiratorial narratives migrate from the margins of the far-right ecosystem into mainstream political discourse.

Yet instead of citing genuine conspiracy theories with which he has compromised himself, Vance chose irony — and performed a polished exercise in stigma reversal. Speaking publicly, he offered the following examples:

“Sometimes I am a conspiracy theorist, but I only believe in the conspiracy theories that are true. [...]

For example, I believed in the crazy conspiracy theory back in 2020 that it was stupid to mask three-year-olds at the height of the COVID pandemic, and that we should actually let them develop some language skills.

You know I believed in this crazy conspiracy theory that the media and the government were covering up the fact that Joe Biden was clearly unable to do the job.

And I believed in the conspiracy theory that Joe Biden was trying to throw his political opponents in jail rather than win an argument against his political opponents.”

He concluded:

“So at least on some of these conspiracy theories, it turns out that a conspiracy theory is just something that was true six months before the media admitted it.”

The manoeuvre is manipulative. Vance strings together three examples that do not, strictly speaking, fall under conspiracy thinking. His opposition to masking very young children was a policy opinion, not a conspiracy theory. Concerns about Joe Biden’s health were widely covered by the media well before his election in late 2020. As for the claim that Biden sought to jail his political opponents rather than confront them politically, this is in no way a proposition later borne out by the facts — contrary to what Vance implies.

The tired argument that conspiracy theories are merely truths that arrive six months ahead of the media serves only to maintain a smokescreen around the very notion of conspiracy theory, allowing the issue to be dodged and attention diverted. Just as a broken clock still shows the correct time twice a day, the fact that a conspiracy theory may accidentally turn out to be correct does not mean one was justified in believing it.

Probably without realising it, Vance here lays bare the underlying way in which he approaches knowledge, truth, and evidence.

Broadly speaking, there are two main ways of understanding conspiracy thinking.

The first is the “classical” approach, associated with thinkers such as Karl Popper and Cass Sunstein. Popper, one of the twentieth century’s most influential philosophers of science and the author of The Open Society and Its Enemies, emphasised falsifiability, rational criticism, and the rejection of closed explanatory systems immune to evidence. Sunstein, a legal scholar and former senior US official, has analysed conspiracy theories as epistemically defective narratives that thrive on distrust, self-sealing logic, and resistance to disconfirmation — the systematic refusal to accept evidence that would normally falsify a claim.

As the British journalist David Aaronovitch puts it, conspiracy thinking rests on “the unnecessary assumption of conspiracy where other explanations are more probable.” This does not mean that every explanation involving a conspiracy is illegitimate. In the minutes following the first plane striking the North Tower of the World Trade Center on 11 September 2001, it was entirely reasonable to hypothesise a terrorist attack — and therefore a conspiracy. In that context, the conspiratorial explanation was the most plausible one available.

By contrast, denying the reality of that terrorist attack and reframing it as an “inside job” amounts to promoting an explanatory framework riddled with insurmountable flaws: a lack of coherence, a lack of evidence, and reliance on layers of speculation and false information, typically propagated by sources known for their unreliability.

The second approach is rehabilitative, or “conspiracy-friendly.” It treats conspiracy theories as just another interpretive framework, arguing that they should be regarded as a rational way of understanding current events and historical reality. Conspiracy theories are viewed from the outset as legitimate hypotheses wrapped in a presumption of insight. Far from being met with suspicion, they are credited with heuristic value, with secret and malicious intent assumed to be among the most plausible explanations — or at least to contain a “kernel of truth.”

Claiming a demanding conception of democracy, the classical approach generally adopts an uncompromising stance toward conspiracy thinking. It treats the fight against conspiracy theories as a civic necessity — a form of public-debate hygiene aimed at preserving the conditions for a democratic space grounded in facts.

By contrast, the rehabilitative approach often caricatures even the most basic criticism of conspiracy theories as a covert attempt to pathologise all “dissenting” or heterodox opinions. It tends to portray efforts to counter conspiracy thinking as strategies of domination — tools of control and censorship that impoverish public debate — while denying that conspiracy thinking itself, toward which it shows considerable indulgence, can function as a powerful instrument of manipulation.

Is it really surprising, then, that this approach now appears to underpin the worldview taking shape in the United States through Donald Trump and JD Vance?

For sixteen years, Conspiracy Watch has been diligently spreading awareness about the perils of conspiracy theories through real-time monitoring and insightful analyses. To keep our mission alive, we rely on the critical support of our readers.