"Repetition does not transform a lie into a truth"

Franklin D. Roosevelt

For every conspiracy theorist figure who has become a household name, there are far more whose contributions to the corpus of fringe beliefs and extremism have been forgotten or lost to time

Many figures whose works formed the basis of modern conspiracism have been usurped by their followers, as conspiracism has become more mainstream and more lucrative.

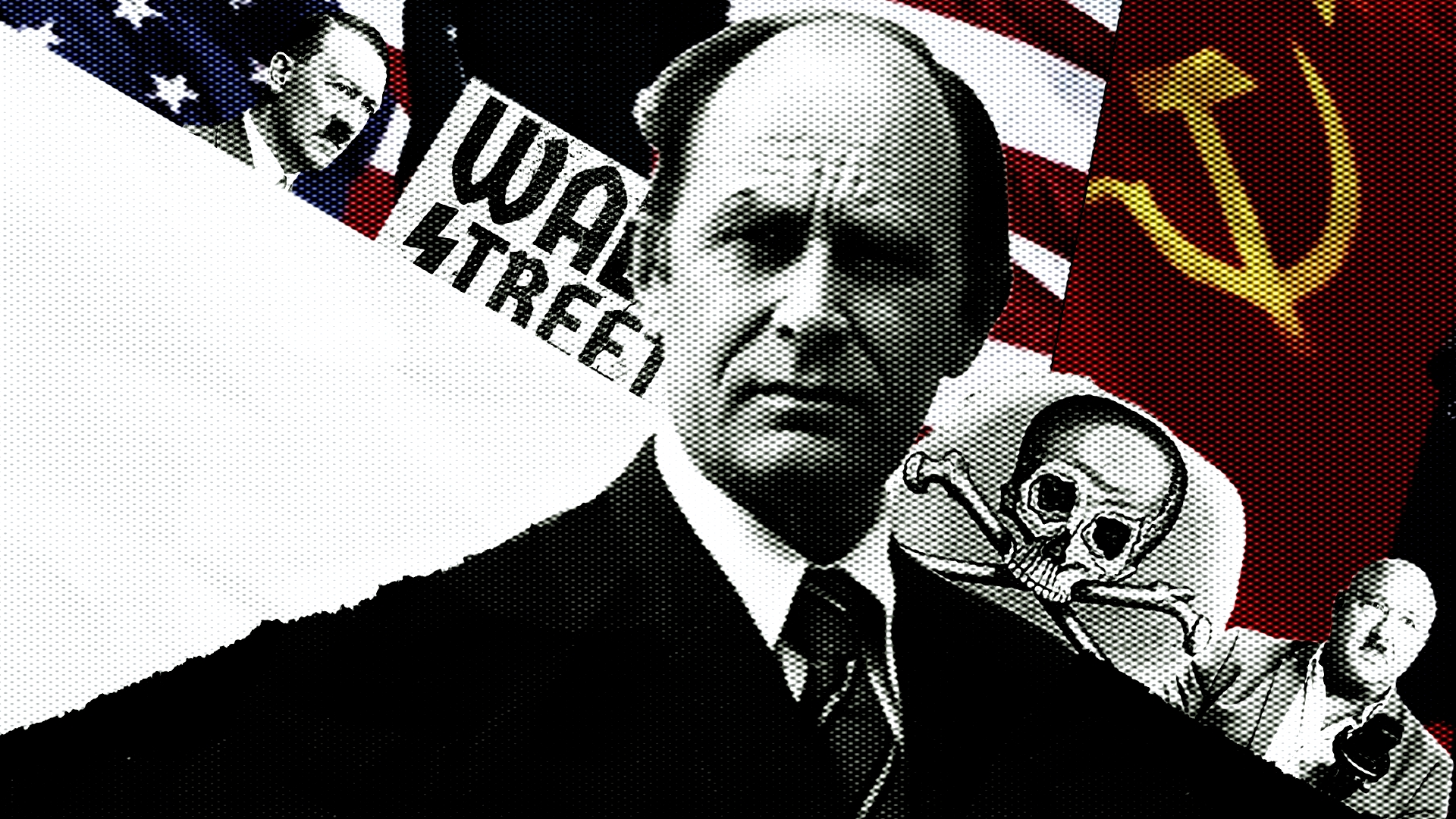

Take British economist and academic Antony C. Sutton who wrote a trilogy of books in the mid 1970’s alleging a vast conspiracy between the United States and the Soviet Union to agitate each other for profit. He claimed Wall Street provided secret funding to Nazi Germany so both sides could make money off the conflict. He wrote extensively about the influence of the Yale secret society Skull and Bones on American politics and military policy. And in the years before his death in 2002, he wrote about supposed secret free energy technology, perceived control of education and economics by a secret cabal, the pernicious acts of the Federal Reserve, and the duplicity of George H.W. Bush.

Every single one of these subjects has formed the basis of the careers of legendary conspiracy figures like Alex Jones, Bill Cooper, David Icke, G. Edward Griffin, and Eustace Mullins. Jones often references Sutton’s books, often misstating his first name as “Anthony.” And while he was an influential figure in the conspiracist movement, he was equally important to the more legitimate libertarian intellectual movement, with connections to think tanks like the Mises Institute and the Cato Institute. His work has been promoted by everyone from Senator Ron Paul and economist Murray Rothbard to Ayn Rand and new age figurehead Elizabeth Claire Prophet.

But Sutton himself remains almost unknown, with his books languishing on the backlists of long-gone publishers, with almost no presence online and few easily-found interviews. How did Sutton’s ideas take such a firm hold in the right-wing fringe even as Sutton himself fell by the wayside? And how did such important works become obscurities?

Born in London in 1925, Sutton earned a doctorate in economics and emigrated to California, where he started teaching economics at Cal State Los Angeles. He later moved to the conservative economic and political think tank the Hoover Institution. In the late 60’s, while at the Hoover Institution, Sutton began work on the books that would define his veer into far right conspiracism.

A three-volume work spanning fifty years, Sutton’s Western Technology and Soviet Economic Development made the shocking claim that the United States had spent half a century helping to build the Soviet Union’s infrastructure and military machine, culminating in a war in Vietnam that may have portrayed a struggle between communism and freedom, but was really the US funding both sides of the conflict through technology transfers and outright payments to the USSR.

Such claims are a common fixture of the right-wing conspiracy movement, usually affixed to powerful Jews being the funders of both sides and aiming to enslave or destroy Christian nations. But Sutton always decried antisemitism, and instead firmly affixed the blame for the conspiracy on the Washington elite – many of whom had links to the Hoover Institution, and were none too pleased with the allegation that the US was secretly funding the battle deaths of US troops.

When the economic and political establishment found Sutton’s work to be somewhere between unfounded and treasonous, he left Hoover, claiming he was hounded out of academia as a whistleblower. “I wish to place on public record that I consider the actions of the Hoover Institution reminiscent of Hitler’s book burning,” Sutton told a US House of Representatives hearing in 1974, though he added that he still had an office and salary provided by the think tank.

But as one of the few figures on the right claiming a vast Soviet conspiracy that didn’t somehow involve the Jews, Sutton became a figure of renown in libertarian and anti-communist circles. Sutton became involved in the Libertarian Party of California and in the far-right John Birch Society. The Birchers had recently endured a series of antisemitism scandals, including the ouster of one of co-founder Revilo Oliver, after Oliver gave a speech decrying a “conspiracy of Jews” and denying the Holocaust.

Sutton gave the output of west coast extremists an academic sheen free of the usual paranoia. But his own work post-Hoover began walking a very thin and familiar line between confrontational and delusional. Publish in the mid 70’s, a second trilogy of books posited another vast conspiracy involving the Soviet Union and the US, this time one of Wall Street bankers aligned with Bolshevik revolutionaries to take down Russia’s provisional government of 1917 and replace it with a socialist nation beholden to the west. That same conspiracy then worked with Franklin Delano Roosevelt to crash the economy, and subsequently funded the Nazis to help pay for the war that made the bankers richer than ever.

To be clear, there’s no evidence any of this was real, and Sutton’s findings are driven almost entirely by anti-communist animus and anti-progressive paranoia. The US government of the late 1910’s and early 1920’s had a mostly hostile, sometimes ambivalent view of the Bolsheviks, and the Soviet Union wasn’t diplomatically recognized until 1933 by the Roosevelt administration – naturally, all part of Sutton’s conspiracy. The US had even intervened in the Russian Civil War on the anti-communist White side, with over 200 US troops killed in combat against Bolshevik forces – a fact Sutton never mentions in the trilogy’s first book, Wall Street and the Bolshevik Revolution.

These three books, full of accusations and rambling statistics, blasted away whatever goodwill Sutton had left with the more mainstream establishment. Within a few years he had been exiled by the right, and made his living writing books on investing in gold, the pernicious influence of the David Rockefeller/Jimmy Carter-founded working group the Trilateral Commission, the potential of cold fusion technology, and on Skull and Bones and its hold over American politics. Many of these topics found homes on the far-right fringe, but little of it was of interest to the think tanks where Sutton had made his name.

Sutton died in Reno, Nevada in 2002, with his academic reputation in tatters and his work mostly forgotten. His high-minded academic style was out of step with the growing body of conspiracist influencers like Bill Cooper and Alex Jones, who used radio shows and the burgeoning internet to spread a flashier and less citation-heavy version of Sutton’s high-minded academic conspiracism.

But Sutton was an influence on all of them. Though his work is hard to find and often hard to digest, Sutton’s ideas had a profound impact on the far-right conspiracy machine. The churn of Skull and Bones theories that have dogged presidential candidates on both sides is a direct link to Sutton, as is the right’s obsession with think tanks and non-governmental working groups as the incubators of tyranny. Driven in large part by Sutton’s writing, the Trilateral Commission became an ever-present scapegoat of conservative conspiracism, serving as a “shadow government” making policy behind closed doors and as part of secret rituals.

His vast conspiracy of a deep state working with America’s supposed enemies to fund wars and keep everyone miserable was really no different than the plots cooked up in later conspiracy theories like QAnon. They all revolve around secret cabals working with the people they’re supposed to be fighting, making money off their lies, and only a few truth-tellers brave enough to speak out against them. What’s today’s “cancel culture” if not a more hyped-up version of Antony Sutton telling Congress that the Hoover Institution kicked him out for his radical revisionism of accepted history?

In particular, Alex Jones would often speak at length about Sutton’s work, placing it on par with the other works that “woke him up” to what the Establishment was “really” doing, books like None Dare Call it Conspiracy and Secrets of the Federal Reserve. As far back as 2003, Jones told a caller he had interviewed Sutton (no interview between the two is publicly available) and recommended his books, while commenting about how difficult they were to find. Jones later gave Sutton credit as the first person to expose Skull and Bones, and at some point began referring to him as the one-time Chief Archivist of Congress, which he was not. Jones still occasionally recommends Sutton’s work, but far less now that Donald Trump is in office, and Jones has begun turning away from many of the ideals he once espoused.

Sutton’s influence can also be found in the merging of the various spheres of conspiracism into one vast conspiracy theory of everything, prevalent in groups like QAnon. For most of the Cold War, there was little mainstream cross-pollination between medical, economic, cultural, and historical conspiracy theories. Or if there was, it was usually in the guise of “things the Jews control,” as seen in the works of someone like Eustace Mullins. Right wing newsletters usually focused on anti-communist activities, but didn’t wade into health conspiracism – except, ironically, sometimes to advocate for vaccination or western medicine.

Sutton, though, was equally as comfortable writing economic pseudohistory as he was writing about political think tanks or free energy. He could have his economic work endorsed by Ayn Rand, while also being interviewed by cult leader Elizabeth Claire Prophet about communism.

While he likely would object to the antisemitism inherent in today’s conspiracy movement, he would almost certainly recognize its reliance on secret government and silent “battle between good and evil” tropes from his own work. And the enmeshment between anti-vaccine, anti-progressive, and anti-establishment groups found in the post-lockdown fringe would be equally recognizable.

All of it points to one common thread: an endless war between truth-tellers and the power elite. This will always form the backbone of conspiracism, even as the supposed truth-tellers find themselves on the same side as the power elite, particularly in the growing influence of conspiracy theories on American governance.

Even though he didn’t live to see it, the influence of Antony Sutton helped make it all possible.

For sixteen years, Conspiracy Watch has been diligently spreading awareness about the perils of conspiracy theories through real-time monitoring and insightful analyses. To keep our mission alive, we rely on the critical support of our readers.